ON MONDAY 25 April, Montgomery was a ghost town. The streets were deserted and the banks and shops closed. Alabama celebrates Confederate Memorial Day every third Monday of April, a day when the soldiers who died fighting for the confederate states in the civil war are honoured.

Senior WJP journalist Ruth Hopkins is spending two and a half months in the United States with the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery and the Marshall Project in New York, investigating the similarities between issues facing both the American and South African criminal justice systems. Ruth will be detailing her journey through weekly blog posts published every Friday.

ON MONDAY 25 April, Montgomery was a ghost town. The streets were deserted and the banks and shops closed. Alabama celebrates Confederate Memorial Day every third Monday of April, a day when the soldiers who died fighting for the confederate states in the civil war are honoured.

Quick history recap: In 1861, the civil war started when eleven southern states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America. This break was caused by the disagreement between free and slave states over the authority of the federal government to prohibit slavery. Montgomery became the capitol of the confederacy and Jefferson Davis the president of the Confederacy.

On Montgomery’s Capitol Hill there is a confederate monument erected in 1898 to commemorate the 122,000 Alabamians who fought for the confederacy during the civil war.

“We have honoured our ancestors,” a woman holding a confederate flag tells me when I approach the monument. Women in hoop skirts and men in civil war uniforms wander around the grounds. An old canon is parked behind an SUV. “We call out the names of soldiers – our great great great grandfathers – who died during the war.” A guy wearing a bandana with the confederate flag and a leather jacket with the same symbol nods vigorously. “We don’t refer to the civil war, but rather call it the war of Northern aggression, or the war of states. We lost the right to decide on our own matters. To this day, the federal government interferes too much in our lives.” When I ask them what kind of matters she says: “gay marriage”. “People say we celebrate slavery, but that’s not true,” the guy with the bandana adds.

Down on the street, protesters disagree. A statue of Jefferson Davis, the president of the confederacy and a slaveholder, stands in front of the Capitol – the same place where on March 25 1965 exhausted civil rights protesters, led by Martin Luther King, reached their end point. A chaotic scene is playing out in front of the building. The police are holding back members of the Black Lives Matter Movement and Black Panthers who, so a television journalist tells me, brought a gun to the protest. They argue that the confederacy was a racist organisation that aimed to preserve slavery, well into the twentieth century, when it became the signature symbol for the Klu Klux Klan and in this century, when pictures of racist killer Dylann Roof surfaced, showing him brandishing a confederate flag in one hand, a gun in the other. A police officer throws the bandana guy a bulletproof vest, which he doesn’t put on.

When Roof shot nine African American church goers in Charleston, June 2015, it sparked a movement to do away with confederate memorabilia in various states. Alabama’s governor Robert Bentley decided to take down four confederate flags from the confederate monument. Despite many states following suit, a recent report by the Southern Poverty Law Centre (SPLC) still documented “1503 Confederate place names and other symbols in public spaces, both in the South and across the nation.’

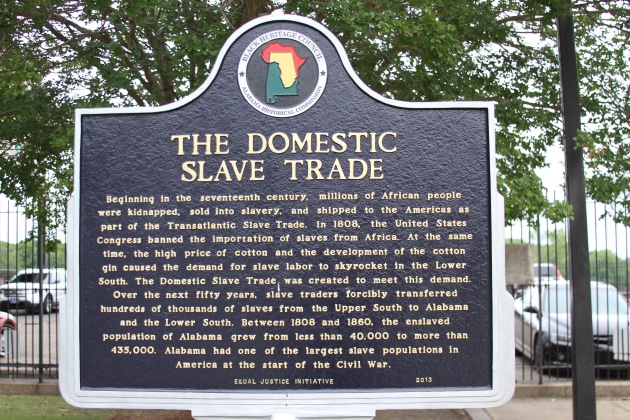

Montgomery, the cradle of both the confederacy and the civil rights movement, is a patchwork of remembrance and conflicting narratives. Advocates of slavery and supporters of white supremacy are honoured alongside the struggle icons, like martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and many others, who fought against the deleterious effects of racial terror. EJI’s office in downtown Montgomery is built in a former warehouse for slaves. This fact is recorded in a marker set up outside the building. It is one of three markers that EJI had to fight to get put up. 59 similar markers around town commemorate the confederacy, but the Alabama historical association deemed EJI’s markers ‘too controversial’. The issue had to be taken up with the mayor before they could be erected. One of them, by the riverside, relates the history of the domestic slave trade and reminds the reader of a crucial fact: “Between 1808 and 1860, the enslaved population of Alabama grew from less than 40,000 to more than 435,000. Alabama had one of the largest slave populations in America at the start of the Civil War.”

Down by the river, the City of Montgomery has put up panels depicting the history of the town and slavery is not mentioned once, while Montgomery’s role as the capitol of the confederacy takes up an entire panel of its own, proudly recounting that in Montgomery: “Confederate leaders sent the telegram ordering Southern troops to reduce Fort Sumter.”

Those two facts; Alabama’s huge slave population and Montgomery’s central role in the confederacy are intimately connected, says Bryan Stevenson, the director of EJI: “The civil war could have been stopped and tens of thousands of lives could have been saved if the federal government had been prepared to say, you can have slavery.”

Openly honouring slavery and slaveholders would not sit well with many people, so the narrative around the civil war changed, says Stevenson. People who initially were called insurgents and traitors were reframed as honourable. “If there were no black people in the state of Alabama, we wouldn’t have this kind of romantic view of the confederacy. They use this fight that started during the civil war, as a way to continue the fight against reconstruction, to fight against land, wealth and equality for black people, to fight against voting rights, to fight against integration, to fight against racial equality and that fight needs a narrative of the honouring the people who were engaged in resistance.” The SPLC points out in their report, that there were two periods in the South were the dedication to Confederate symbols spiked, during the first two decades of the twentieth century, when the Jim Crow laws were introduced and in the sixties, during the civil rights movement.

While the crowd on the hill looks harmless and a little bit hideous in their historical outfits, it is anything but a quirky habit of amateur historians, warns Stevenson. “It would be the same if you said, you know we should create a new narrative about the Second World War, the Nazis weren’t bad, they weren’t evil, they were dedicated, they were committed to Germany and we should celebrate them and honour them. Hitler was just passionate, he was committed to Germany and we should respect him.”

In Montgomery the narrative of a proud confederacy is visceral and dominant and is echoed in its street names, buildings, signs and statues. But EJI, instead of protesting the display of Southern pride and honour, has started an elaborate and ambitious remembrance project that not only includes the collection of soil from sites of lynchings to remember the victims. It also encompasses a museum that is currently being constructed at the back of EJI’s building, dedicated to the evolution of slavery into mass incarceration, as well as a memorial monument that is going to be built to remember victims of lynchings. EJI has bought the land and enlisted the help of an architectural firm. During theannual benefit dinner in New York, Stevenson presented a video of the project. Columns representing people who died from lynchings, slowly become suspended from above, evoking the ‘strange fruit’ hanging from trees. The columns will be filled with soil from the towns and cities where the lynchings took place and. These towns will be offered the opportunity to take the column and display it as their own remembrance, thus ensuring the narrative of pain and suffering is not forgotten.