Ahead of SA’s watershed 1994 election, 3-million hectares of KwaZulu land were transferred into the Ingonyama Trust, under the Zulu king. On November 22, the high court in Pietermaritzburg will hear residents who claim they have been unlawfully forced to pay rent to the trust, which, aside from having never received a clean audit, appears to be predatory and intimidating.

The Umnini holiday resort in the south of KwaZulu-Natal has a picture-perfect view. The 21-chalet resort, with a 40-seater conference venue, overlooks Umgababa beach, where waves from the Indian Ocean crash on the sand.

It would fit right into a glossy tourist brochure, if it weren’t for the obvious disrepair and dilapidation. The buildings have been vandalised: roofs are missing, grass and weeds are reclaiming the structures. A green succulent is growing inside a disused and broken toilet bowl, crawling ivy climbs a wall that is slowly disintegrating.

It’s a tragic story, which serves as a metaphor of the fault lines in SA’s ever-elusive land reform process. It shows how well-connected political elites have grabbed the advantage for themselves, even as millions of South Africans remain without land.

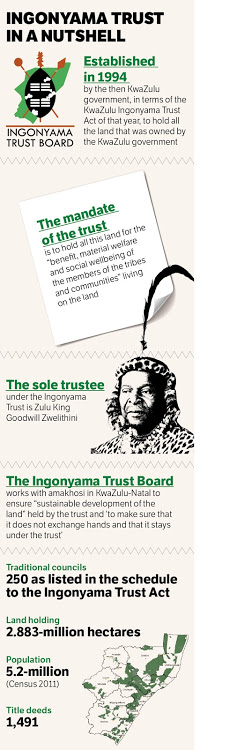

And it’s an indictment of how the Ingonyama Trust — a private body set up in 1994 to administer 2.8-million hectares of former apartheid homelands on behalf of its sole trustee, Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini — appears to have abused its power without being held accountable. And it has failed to provide land and prospects for the 5.2-million people who live on that land.

The story of this holiday resort dates back to the days of grand apartheid, when beaches were still segregated. At the time, Umgababa, which is about 30 minutes south of Durban, was one of the few resorts where black people could vacation.

In 1981, a student named Edward Mpeko visited Umgababa and fell in love with the place. “It was quiet and beautiful, a place where black people could hold meetings because it was off the police’s radar,” he says in an interview with the FM.

In 2001, by then a successful businessman, Mpeko returned with grand plans. “I wanted to revive this place,” he says.

So he sold all his properties and invested in a bar, a B&B and a restaurant at the holiday resort. Once he moved in, he started building the conference venue. When he bought the property, it looked much like it does today. “There was no water or electricity, the walls were crumbling,” he says.

But in 2012, when the Umnini holiday resort began flourishing, the story took a dark turn. Jerome Ngwenya, a former judge and chair of the board of the Ingonyama Trust, arrived at Mpeko’s door and told him he had to pay an annual “rent” to the trust.

Ngwenya’s argument was that even though Mpeko had bought the property, the Umgababa land falls under the separate “Umnini Trust” which was established in 1858. But Mpeko says he was already paying the local chief R1,000 a month and he had a “permission to occupy”, or PTO — an apartheid-era right to reside on the land.

But Ngwenya kept harassing him. Mpeko says he was attacked and threatened, and had to sleep with a knife under his bed.

Then in 2013, Ngwenya and the local inkosi (chief) Phathisizwe Luthuli arrived at the property with a sheriff in tow. The sheriff presented Mpeko with an eviction order.

“They told me that there is no place for a Basotho man in this Zulu place,” he says.

Dozens of security guards, who accompanied Ngwenya, picked up Mpeko’s possessions and threw them into the road. Mpeko fled and supporters of the inkosi looted and vandalised the property.

Though a court had initially ruled Mpeko was in arrears and could be evicted, this was reversed by the high court in Pietermaritzburg in 2015. But by then it was too late.

Mpeko says he is a “broken man”.

Mpeko’s case is one in a long list of people whom the Ingonyama Trust is alleged to have threatened, harassed and sued.

According to the Ingonyama Trust Act, the trust is supposed to administer the land “for the benefit, material welfare and social well-being of the members of the tribes and communities”. In SA, land allocation and distribution are governed by customary law, which is recognised in the constitution.

As researchers with the Mzala Nxumalo Centre for the Study of SA Society in Pietermaritzburg write about customary law: “Land was owned collectively, as it belonged to the isizwe (the ‘nation’) chiefdom. The king or chief merely acted as its custodian.”

Land allocation was a balanced reciprocal system that had evolved over centuries: “Under the practice of ukukhonza (paying allegiance to a chief or king), the abanumzane (homestead-heads) were allocated sites on which to establish their imizi (homesteads), to cultivate and for their livestock to graze. In return they, and members of their homesteads, were expected to fulfil certain civil duties,” they write.

Colonialism disrupted this finely balanced set of rules and customs. The British decided to vest ownership rights with trustees, mostly headmen and inkosis, because they reasoned that individual ownership of land was not recognised. The colonial and apartheid-era policy of “divide and rule” was to legitimise certain traditional leaders in order to control the people. Chiefs were benefited and others excluded, depending on their usefulness to the colonial authorities or the apartheid government.

The Ingonyama Trust Board is in many ways a relic of this colonial past. It is charging rent to people who have a pre-existing communal right to live on the land. It has bullied and threatened businessmen like Mpeko, as well as farmers and other residents, while leasing off large chunks of land to multinational corporations that have little or no concern for the people who live on the land. While government bodies are aware that the trust is not honouring its obligations, they have done very little to address the irregularities.

This indifference probably stems from the powerful political pull that King Goodwill has on SA politicians. The trust was formed only in 1994, days before the apartheid government handed over power to the ANC. Some argue it was created like this — with the king as the sole trustee — as a quid pro quo to entice the IFP to participate in the 1994 elections, after Mangosuthu Buthelezi threatened a boycott.

A 1997 amendment to the enabling legislation later created the board of the Ingonyama Trust. While land held in other homelands in SA was transferred into a trust governed by the state, the Zulu king and the KwaZulu homeland were awarded a “status aparte”, or special status, because of fears that the king and his political ally, Buthelezi, would trigger a civil war or even secession.

This political leverage is still effective today. In 2018, former president Kgalema Motlanthe chaired a high-level panel that produced a report on the constitutionality of a raft of laws, including the Ingonyama Trust Act, adopted post-1994, assessing their contribution to “the acceleration of fundamental change”.

One of the panel’s most controversial recommendations was “the review of the Ingonyama Trust Act with a view to repeal or to amendment”.

King Goodwill Zwelithini lashed out in response, threatening that “all hell will break loose” if the recommendation was carried out. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s reaction was instructive: he scrapped all his official appointments and rushed to bend the knee before the king.

“I assured him that [neither] government nor the ANC has any intention whatsoever to take the land from the Ingonyama Trust,” Ramaphosa told reporters afterwards.

But politicians won’t have the final word on this divisive issue. On November 22, the high court in Pietermaritzburg will hear residents who claim they were unlawfully forced to pay rent to the trust.

Hletshelweni Linah Nkosi is one of those claimants. When the FM visits her, she’s feeding a young goat with a bottle in one hand while chatting to someone on her cellphone in the other. About 30 loudly bleating goats are in a pen behind her.

Behind her, there’s a view of the valley: a lush countryside, dotted with rondavels. It is calm and quiet and the air simmers with a pleasant heat. Chicken, goats and sheep graze in the green strips next to the road.

Nkosi’s property is a smallholding in Jozini, in northern KwaZulu-Natal. She bought it in 1974, when her family approached the local induna to ask permission to settle in the area. In a traditional ceremony, meat and beer were exchanged and the family was given permission to settle. A small khonza fee was paid, a nominal amount that is supposed to cover administrative responsibilities of the land allocation.

In 2011, Nkosi was handed a pamphlet being distributed in her neighbourhood.

It described a new system of leases that the Ingonyama Trust was going to introduce.

Ngwenya’s phone number was listed on the paper.

Most residents in Jozini had previously acquired the apartheid-era PTO. The Ingonyama Trust officials told Jozini residents that a lease was a more modern and therefore a “better right to have”.

Says Nkosi: “I decided I would sign a lease because they told me it would be much easier to apply for a loan with the bank if I had a lease.”

As a businesswoman, she also runs a funeral home and a meat business. But when she presented herself at the traditional council to sign the lease, they told her that the Ingonyama Trust wouldn’t allow a woman to conclude a lease on her own. Nkosi was not married to her then boyfriend. And she’d financed the construction of the three houses on her property herself.

The trust told Nkosi that if she didn’t sign the lease, it would reduce the size of her property. In the end, she and her partner signed for the lease — but she has, to this day, refused to pay the trust any money. “I said I would not pay for the lease, because that would authorise my boyfriend as the official owner of my properties. They were oppressing me as a woman,” Nkosi says.

The lease also contained other clauses that were never explained to her. For example, the trust could increase the R1,600 rental amount by 10% a year. And if the lessee stopped paying rent, he or she would lose the land and all properties on it, as the trust retained a right to dispossess.

Over the years, Ingonyama Trust officials have visited Nkosi regularly and have threatened to either cut the size of her property, or boot her off the land entirely. So when Nkosi heard about the case that lawyers with the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) had started on behalf of other Jozini residents against the trust, she leapt to join them.

A few minutes down the road from Nkosi’s property, Mabongi Gumede lives on her plot with her sisters and their children.

Gumede shows me the five homes on the plot that she and her sisters have built. A few chickens pick at the dirt, but otherwise there is no livestock here, because most of the women living on the property have jobs that take them away from home. Large tombstones rise above the wild grass and weeds. Gumede has buried her mother, sister, daughter and nephew on the grounds.

Around 2011, the “induna police”, as Gumede called the Ingonyama officials in her affidavit, threatened to throw her off her land if she failed to pay rent. Gumede decided she would pay for a lease, to secure her property. But she was shocked to see the annual rent amount: R2,900. She had never paid rent since she moved in during the 1970s. In her affidavit, Gumede says: “I do not fully understand what it means to have this lease, but I do know that I do not want it.”

On a hot day in Jozini, in the shade of a tree, Gumede fans herself with a copy of that lease and tells the FM: “I want this document to be cancelled.”

Hluphekile Bertina Mabuyakhulu has lived next door to Gumede for decades. In 1982, Gumede introduced Mabuyakhulu to the traditional council, which gave her permission to settle there with her children.

When we visit, her helper meets us at the gate and brings us to Mabuyakhulu, who is sitting on a blanket on the floor in one of the houses. A stroke had rendered her immobile and unable to continue growing vegetables or speak clearly.

She is a pensioner and struggled to make ends meet even before the stroke.

As was the case with Nkosi, the Ingonyama Trust had also visited Mabuyakhulu several times since 2011, urging her to sign a lease with them. Though she signed, she never paid the rental amount. Now she lives in fear of being evicted from her property, where she has lived for many years, raising children and grandchildren.

Another Jozini resident, Bongani Zikhale, is also a claimant. He is a physically imposing man in his late 50s, who also recently suffered a stroke. While his speech is slurred, his indignation is clear.

But his legal position is slightly different to the women’s: Zikhale lives in Jozini township and, according to several laws, including the 1997 amendment to the Ingonyama Trust Act, rural townships are excluded from the ambit of the trust.

Yet despite this legal provision, in 2011 Ingonyama Trust officials told Zikhale he needed to sign a lease and start paying rent. Zikhale initially agreed to sign, because he says he trusted the local traditional leadership. But his indignation grew when he saw the contract’s stipulations: the rental amount, the 10% increase and the eviction clause.

“What am I,” he asks, raising his voice. “A foreigner in the land of my ancestors?”

To make the situation worse, the Ingonyama Trust has claimed other land that was officially excluded from its mandate. In 1994, the KwaZulu-Natal government transferred the Umnini Trust in its entirety into the Ingonyama Trust, though it never belonged to KwaZulu and didn’t fall under the SA Development Trust (an apartheid-era state institution that formerly owned all land in the homelands). Residents in Umnini have PTOs, yet face pressure from the Ingonyama Trust to pay for leases.

In the Denny Dalton area, close to Babanango in the northwest of the province, nine old men have gathered in a community hall with sweeping views of the valley below.

The men look as if they have been working the fields: some have torn jackets, others have sprigs of straw stuck in their hair. One by one, they stand up and vent their anger. They point out that since 1951, the community paid the SA Development Trust a set amount every year until 1997, when they were told they did not need to pay any more.

But in 2011, an induna who was not from the area started allocating land to outsiders without the consent of community members. When challenged, he said he was “the eye of the king”. He charged fees 10 times larger than the usual amount — and that money didn’t end up with the traditional council.

In 2017, residents went to the provincial department of rural development & land affairs to protest against this situation. The department referred them to the Ingonyama Trust as the rightful owner of the land.

Aware of the brewing tensions, the trust called a meeting with the Denny Dalton residents in Ulundi, where Ngwenya showed up with several amakhosi. Though Ngwenya promised to talk to the king about the matter, he never got back to the community. And when community members asked the Ingonyama Trust for proof of ownership of the land, it failed to provide this.

The problem is that today, the men say, they feel threatened because they have lost control over land which they and their ancestors have lived on for centuries.

Basil Bhekani Sibiya’s experience is an even more blatant example of this kind of “land grab”. He lives on the privately owned Impaphala lots in the Eshowe area.

Sibiya was born on the land and his forefathers lived there for generations. In 1908, American missionaries working for the United Congregational Church (UCC) of SA bought the Impaphala lots (each about 12ha in size) from the government. The 85 families living on the lots paid a nominal rent to the UCC. The Impaphala lots never belonged to a homeland and so were not transferred into the Ingonyama Trust in 1994.

But in 2007, a new inkosi, whom Sibiya knows as ZM Biyela, joined the Mvuzani traditional authority in the area. He said the Impaphala lots belonged to him and to the Ingonyama Trust, and started farming on the land. When Sibiya pointed out that the lots were privately owned, the chief became angry. He was even more irate when Sibiya presented him with a letter from the provincial department of co-operative governance & traditional affairs (Cogta), affirming Sibiya’s claim. Cogta officials visited the site and said the inkosi could not farm on the land of the residents of the Impaphala lots.

Cogta, however, did little more than write that letter and visit the site. When Biyela started grazing his cattle on Impaphala land, it did nothing to stop him. And when the Ingonyama Trust and Biyela entered into a deal with sugar producer Tongaat Hulett to start growing sugar cane on the Impaphala lots, Cogta said nothing.

In 2015, the Impaphala residents visited the Ingonyama Trust to discuss the situation. Trust officials advised them that leases with the Ingonyama Trust would protect them against people like the inkosi. The residents, however, refused to sign these leases because, they said, the land was theirs. Which led to a stalemate.

As it stands, Biyela still feels entitled to the Impaphala lots and the situation with Tongaat Hulett remains unresolved.

Asked by the FM to answer 23 questions in recent weeks, the trust acknowledged receipt, but answered nothing.

The issue is, why has the Ingonyama Trust not been held accountable for forcing leases on residents and allegedly grabbing land that never belonged to it?

When responding to criticism that the Ingonyama Trust has been subverting a centuries-old communal system of land allocation by imposing “leases”, the trust’s chair, Ngwenya, usually flips the script. In the trust’s 2017/2018 annual report, Ngwenya writes about individual title deeds: “Individuals, once they get title deeds, they will pledge them with the loan sharks. At the same time, some municipalities will access land at a bargain upon default of rates.”

Ngwenya claims leases “are consistent with a customary law approach to land ownership”.

It’s a remarkably paternalistic and patronising argument, especially since the trust and its board have never received a clean audit from the auditor-general (AG) — despite a sharp growth in the amount it is collecting from “leases”.

In 2006/2007, the trust recorded income from leases of R14m; 10 years later, this has increased dramatically. In the 2017/2018 annual report, income from leases grew to R109m in 2017, before slipping back to R93m in 2018. This suggests the motivation to introduce a system of leases was never about applying a “customary law approach”, but about making money.

Ngwenya almost admits this in the 2007/2008 annual report: “The PTO system did not generate much funding for the board; instead the board was a liability to the state in terms of its running cost. However, since the shift from the PTO system to lease, the revenue of the board had gradually increased.”

Some parliamentarians seem to have noticed in recent years that not all is right with the Ingonyama Trust.

In 2013, in front of parliament’s portfolio committee on agriculture, land reform & rural development, the trust was roasted for underspending its budget, while overspending on issues that appeared to fall outside of its mandate. For example, that year, it spent millions building houses for traditional leaders who, as it happens, also received a salary from the government.

Parliamentary minutes recorded ANC MP Phindisile Xaba posing some awkward questions about how the trust hadn’t helped lift people out of dire poverty. “She asked what exactly the Ingonyama Trust board was doing … [it] should be doing more to help their people,” the minutes record.

But since the trust was never properly held accountable, some of its spending decisions have been even more outrageous. In 2015 it used R2m of its R20m government budget to buy the king a new car.

In 2016, the AG gave the trust an “adverse opinion”, which means certain figures were misrepresented in the accounts. One recurring problem was the financial surplus, which stood at R55m in 2015. Despite this surplus, the trust kept asking parliament to raise its budget. At the same time, it was underspending its budget, by up to 50% in some years.

This financial tension came to a head in 2018 when the trust received another adverse opinion from the AG. Parliament then ordered the Ingonyama Trust to stop converting PTOs into leases. That year, the trust spent a whopping 95% of its budget on administration, with only 0.16% and 0.11% going to rural development and land management, respectively.

In other words, the board members blew nearly the entire budget on themselves, drip-feeding only a tiny amount to issues supposedly central to the trust.

The language in parliament began to change. “[Some MPs] do not know why the government is pussyfooting around KwaZulu-Natal since 1994 by allowing the establishment of the Ingonyama Trust board, yet other provinces do not have a trust of similar nature,” the minutes reflect. Elsewhere, some MPs remarked that the trust’s board is a “banana entity and a law unto itself”.

Certainly, it seems that Ngwenya, the central figure in the Ingonyama Trust, has behaved with impunity. He seems to believe few laws apply to him or his various business enterprises.

Consider this tale of self-dealing: he is a shareholder in a real estate company, Ketshe Investments. In 2012, Ketshe had no problem scoring a “land availability agreement” on trust land. However, as the AG reported in 2018, “there is no consideration for land availability agreements in terms of the board’s policy”.

Ngwenya also owns Zwelibanzi Utilities, which runs a petrol station in Adams Mission. By 2018, that company was in arrears in its lease payments to the trust of R281,779. Despite that, the short-term lease for the petrol station was converted to a long-term business lease, violating the trust’s policies.

Lastly, Ngwenya is a shareholder in Zulu-land Anthracite Colliery, an anthracite mine on Ingonyama Trust land.

Both King Goodwill Zwelithini and Ngwenya are shareholders in Bayede Marketing, which sold wine to the staff of the Ingonyama Trust. When Ngwenya admitted this in parliament in 2014, it caused widespread outrage.

This suggests there is one set of rules for Ngwenya and the Ingonyama Trust board, quite another for everyone else. In the same vein, Fikisiwe Madlopha (the former acting CEO and a consultant to the trust’s board) owns a company called Mkathi Manufacturing and Distributors, which owes R13,000 to the trust in lease arrears.

In this context, it seems deeply unjust that while the trust’s board members behave with impunity, someone like Edward Mpeko, who bought the Umnini holiday resort at Umgababa and built a business on it, was forcibly ejected.

Ramaphosa, desperate to shore up his splintering political support, has shown no stomach for tackling the abuses by the Ingonyama Trust. Now finally, it might be a court that decides to hold it accountable.

First Published in Business Live

Main Picture: Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini and Mangosuthu Buthelezi. Picture: RAJESH JANTILAL/Getty Images