When American police officers shot dead two black men – Anton Sterling (Batton Rouge, Louisiana) and Philando Castile (Falcon Heights, Minnesota) – within 24 hours in the sweltering heat of July, thousands took to the streets to protest against the violence that they say is predominantly aimed at African-Americans. Two days later, a sniper killed five police officers, who were guarding a demonstration in Dallas, Texas. His aim? To kills as many white cops as possible.

The reciprocal violence exposes a raw inflamed wound, where many hoped there was a scar. Has Martin Luther King’s dream evolved into a nightmare? In 1903, sociologist and chronicler W.E.B. Du Bois presciently wrote that the problem of the 20th century would be the problem of “colour line”, the invisible line that divides the darker and lighter races in America. Despite King’s civil rights movement, which has found a worthy successor in the Black Lives Matter movement, achievements such as desegregation in schools and the first black president in the White House, the colour line seems sharper than ever.

And although awareness of institutional racism – see for example Beyoncé’s and Kendrick Lamar’s protest performances against the mass incarceration of people of colour – is growing, the reality on the ground is refractory.

New York has the nation’s largest police force, the NYPD, and is also one of the most racially mixed cities in the country. The men and women in blue and the black and brown communities are frequently at loggerheads.

Delrawn Small died on a sidewalk in Brooklyn on Independence Day, 4th July, after a police officer in plainclothes shot him following a dispute about a traffic violation.

A few days later NYPD Police Commissioner William Bratton added insult to injury. During a radio interview he blasted the Black Lives Matter movement, which gained national and international fame with demonstrations against police violence against black people. Bratton said that the activists should stop “yelling and screaming at cops about police brutality because it accomplishes nothing.” This led to the occupation of City Hall Park under the banner #ShutDownCityHallNYC, where protesters demanded Bratton be fired because he is a racist. They rechristened City Hall Park as Abolition Square.

To everyone’s surprise – but certainly not as a result of the protests, Mayor Bill de Blasio promises – Bratton resigned on 2 August. Some breathed a sigh of relief that his controversial term had ended, while others were sad to see him go. He is credited in law and order circles for stemming soaring crime rates in New York City in the 1990s, during his first appointment as NYPD commissioner. But his opponents say Bratton’s approach has led to a drastic deterioration in race relations between the police and people of colour in New York.

Those detractors viewed Bratton’s reappointment as police chief in 2014 with suspicion. Progressive mayor De Blasio won the elections with a promise to improve relations between the police and minorities in the city.

From that perspective, Bratton’s appointment was indeed a strange choice. He is the architect of “Broken Windows”, an approach to crime reduction he embraced as NYPD boss in the ‘90s. Broken Windows led to aggressive surveillance, investigation and enforcement of minor offences committed mainly by people of colour. The theory is based on the premise that minor violations of the law, such as a broken window, adversely affect social cohesion and thus produce more serious offences. The rationale behind the doctrine is that crime rates will go down if you tackle all offences equally thoroughly. Although the Broken Windows theory is theoretically colour-blind, formally not aimed at a particular group, it did not work out that way in practice.

Bratton’s approach led to over-policing of mostly minorities, who were stopped, searched and often arrested on street corners. There is no objective reason to supervise these groups more. For example, while the rate of drug use among whites and non-whites is roughly the same, African-Americans are detained and arrested much more frequently. A 2014 study published by the American Psychological Association furthermore found that police view black children and youngsters as older and more dangerous than their white peers.

Human rights lawyer Chaumtoli Huq was arrested in 2014 on “broken windows” grounds. On a sunny summer day in Times Square, Huq, a Bangladeshi-American, had her face and body pressed against the window of a restaurant.

“I shouted, ‘I’m not resisting the arrest. I’m not resisting the arrest’.”

When her husband and two children returned from a visit to the bathroom in the restaurant they saw her shoe lying on the crosswalk. Huq had been pushed into a police car.

That day, Huq and her family had attended a demonstration on Times Square against the Israeli occupation of Gaza. Times Square was a manic hustle and bustle of demonstrators, tourists and New Yorkers. The police officer arrested her after he had told her to move from the sidewalk and she had explained to him that she was waiting for her husband and children to return.

“He pressed his lower body against my pelvis, I could not move. After he twisted my arms behind my back, he pushed them up, so I could only walk bent over.”

In the car on the way to the police station, the officer grabbed Huq’s identification from her purse. “I’m a lawyer, so I told him that was not allowed without my permission. He then said to me: ‘You are my prisoner, I can do what I want.’” Months after the arrest Huq still suffered from insomnia and a feeling of discomfort, “like I was sexually assaulted”.

But it could have ended much worse. Exactly one day earlier, on July 17, 2014, Eric Garner was also standing on a sidewalk when a New York police officer, Daniel Pantaleo, approached him. He accused Garner of selling illegal loose cigarettes and Pantaleo tried to handcuff Garner. When the tall Garner pushed Pantaleo’s arm, the officer grabbed him in a chokehold from behind, around his neck. Chokeholds were and are prohibited within the NYPD. Garner fell to the ground with Pantaleo still holding him. Five other police officers stood around and watched. They heard Garner’s last words: “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,” which became the rallying cry of the Black Lives Matter movement. Garner died some time later.

Garner put the Big Apple’s racial divide between black and blue on the map. His death was widely reported in the media and was one of the first high profile cases the Black Lives Matter movement rallied around.

Since then, the NYPD has tried to improve relations with the communities. It has designed new guidelines around the use of force by police officers. The new policy includes improved definitions, streamlined research and better documentation and monitoring of the use of force.

But the real problem is much more deep-seated than a chokehold, says Edwin Raymond. Raymond works as a police officer in “transit”, which means his workplace is the vast web of New York’s underground subway transportation. Last year he joined the “NYPD 12”, minority officers who started a lawsuit against the NYPD because, so they say, they were deemed to comply with “inherently racist” quotas for arrests.

“Officers are expected to hide in broom closets, refuse rooms and rest rooms. The doors in these rooms have vents and officers would have to peek through the vents.”

According to Raymond his superiors expected him to hide in these rooms so he could arrest unsuspecting commuters for minor offences, such as “jumping the turnstile”. People who can’t afford train tickets are usually poor and non-white New Yorkers.

Annabelle*, a 33-year-old black writer, whose stage name as a rapper is Ginger, was late for an appointment a few years ago. At the turnstiles, she found her card wasn’t working properly.

“The machine spat out my card, because there was not enough money on it, but I had just paid. So I jumped over the turnstile and out of nowhere a cop appeared. I tried to explain to him what had happened, but the handcuffs were already around my wrists.”

The cop arrested Ginger and she was transported to a police cell in “the tombs”, a large complex of police cells in Manhattan, and then on to New York’s largest prison, Rikers Island. Her stay at the notorious detention centre lasted only three days, but has had a huge impact on her life as it resulted in a criminal record. At the time, employers were allowed to run a check for criminal records before interviews. Ten months ago, that changed and employers can only do a background check after they have offered the applicant a job. Finding work was practically impossible for Bird: “I would apply everywhere, but would never hear back from them.” Ginger now works at a direct-sales company, selling energy contracts door-to-door. Some months later she still doesn’t earn enough for the subway fare to get to work.

Raymond, the whistle-blower, knows the negative spiral that many black youth end up in. Its trajectory is a sequence of negative steps: a young person wants to apply for a job or go to school, but skips the fare because he or she has no money for a subway ticket. He gets caught because the police have to produce a certain number of arrests, this leads to a criminal record for the kid and as a result he will have a hard time finding work and education. Raymond, who still works as a cop, said: “I never participated in this quota system. I went out there and I policed properly, I used discretion and would arrest people when I had to.”

Raymond’s stance on the issue first led to friendly “chats” with his superiors, then his application for overtime and leave days would be rejected. “I’ve seen people being slammed to the floor just because they spat on the floor, took up two seats in the train or because they were kissing their girlfriend goodbye and were blocking the turnstiles. They are arrested just because you need a day off or you need overtime. And these quotas barely exist in white neighbourhoods.”

Raymond’s ultimately refusal led to dismal work evaluations, which are crucial to career progression.

Whether or not there is a possible quota system is a sensitive issue because of the profound implications of the lawsuit Floyd vs New York. David Floyd, a young African-American, was one of the plaintiffs in a collective civil lawsuit against the city of New York in 2013. The city was held responsible for ethnic profiling and unconstitutional stopping and frisking people of colour. The case exposed a racist undercurrent within the police. It led to compensation for the victims, but also to a federal monitor – a supervisory body – which issues reports on the issues that were central to the lawsuit.

The figures support Floyd’s and Raymond’s experiences and allegations. Preeti Chauhan, a researcher at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, conducted a study in 2013 on the demographic composition of people who were arrested for misdemeanours. The research concluded that non-white males between 18 and 25 years were three times more likely to be detained and arrested compared to white men in the same age group.

Raymond, who grew up in East Flatbush, an African-American neighbourhood in Brooklyn, knows what this feels like. He lived in a small apartment with his brothers and single father who had emigrated from Haiti to the Promised Land.

“One day a group of officers in plainclothes jumped out of a car and threw me against the fence and started going through my pockets. I was shocked and put my hands up and asked ‘what did I do’ and I was told to ‘shut the fuck up’. They let me walk and it was just such a traumatising experience, because, on the corner the actual criminals in the neighbourhood were watching me and I remember thinking the police have to be racist, because the only thing I had in common with the criminals was our race. Later, as a police officer, I would learn that officers are required to get a certain amount of stop and frisk.”

That Raymond and his co-plaintiffs complain about a racist system of ethnic profiling is a sign that the comprehensive system of control and accountability that Floyd created is not functioning properly.

A recent ruling by the Supreme Court, Strieff, offers little hope for change. With a narrow majority the Supreme Court decided in June that an arrest, search or interrogation of a person, conducted without reasonable suspicion of a criminal offence, can be deemed legitimate if it turns out there is an outstanding fine or an earlier offence committed by that person. Such a flexible interpretation of the law will lead to ethnic profiling and excessive use of stop and search, Judge Sonia Sotomayor wrote in an exceptional dissenting opinion. Sotomayor broke an unwritten rule: she explicitly mentioned the problem of the racial bias of the law. She not only referenced W.E.B. Du Bois, but also contemporary authors Ta-Nehisi Coates and Michelle Alexander, who wrote the groundbreaking The New Jim Crow, on the racial bias of the criminal justice system in the US.

While ethnic profiling has thus become easier at the federal level, the NYPD is trying to mend broken down relations at the city level.

In 2013, Bratton appointed Susan Bratton Herman, a deputy commissioner, to head the department of collaborative policing, with the aim to heal the damaged relationship between blue and black, before guns are drawn or chokeholds applied. Herman explains in her office at Police Plaza, the NYPD skyscraper in downtown Manhattan:

“Collaborative policing is about promoting shared responsibility for public safety.”

Herman works with other departments within the police, city services, but also with the community: residents, activists and religious leaders. Her department launched an initiative in four police districts where 1,300 police officers are exempt from 911 emergency calls. They are instructed to start conversations with locals, to be a visible presence and to co-operate with shelters for battered women and the homeless. Collaborative policing has also led to Ceasefire, an initiative in North Brooklyn where gangs and crews who are responsible for shootings and murders take a seat at the table with local residents and the NYPD.

Herman hopes to address violence crimes through conversations and the power of communication. The NYPD could not produce figures on the impact of these projects. Herman’s office is also closely involved in changing the policy around marijuana possession, moving away from arrests and instead issuing a summons. Since the new policy was introduced, marijuana arrests have declined by 40%, according to an NYPD spokesman.

These and other reformed enforcement policies have reduced the number of arrests and enforcement interventions. But the question is whether the reforms really address the problem, because despite new policies, minorities are still targeted disproportionately. Sotomayor’s groundbreaking dissenting opinion was so remarkable because she explicitly mentioned race. Race and racial discrimination are rarely mentioned in policy reforms. As a result, it is possible that the number of arrests drops, but the tripled risk of arrest for young non-Caucasian men can continue to exist. Despite extensive reforms at Rikers Island – the prison population fell from 25,000 to 8,000 over two decades – 95% of the population is still black or Hispanic. The Reforming Police Organising Project (PROP) produced a report a few months ago on 524 broken window charges (among others disorderly conduct and marijuana possession) that came before in courts in Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. Approximately 90% of the suspects were black or Hispanic, which is an indication of an underlying racial prejudice.

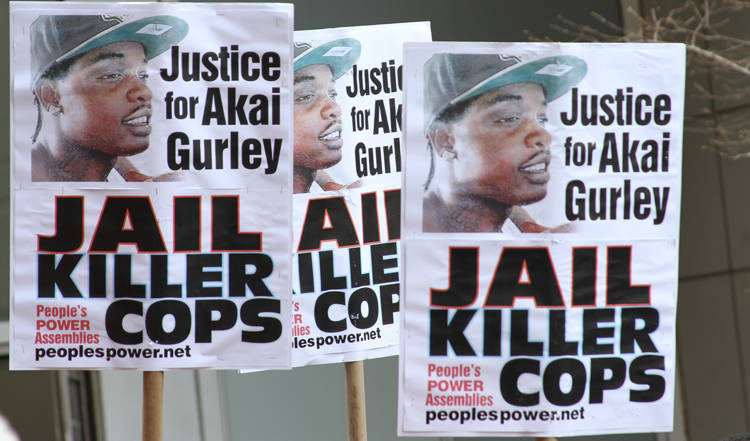

The anger about the injustice of these figures was palpable when in April of this year, Ken Thompson, a prosecutor in Brooklyn, advised a judge not to impose a prison sentence for Peter Liang. In 2014, Liang, a young police officer, shot and killed Akai Gurley, a young black man. Gurley lived in one of the projects in East Brooklyn, a predominantly African-American district that is regularly patrolled by the police. Liang came up a dark stairwell, with his finger on the trigger, when he heard a strange noise. He fired his gun. The bullet ricocheted against the wall and landed in Gurley’s chest. When Liang was charged and found guilty of manslaughter it caused a stir, because until then barely any police officers had been prosecuted, let alone convicted, for the shooting of a civilian. But the hope that change was afoot soured when Thompson recommended that house arrest and community service were a more appropriate form of punishment.

Nicholas Heyward Senior, a tall man with a gold front tooth, stood in the crowd in front of the DA’s office and shouted along with angry protesters, “NYPD, KKK! How many kids have you killed today?”

Heyward lost his 13-year-old son, also named Nicholas, 22 years ago when an inexperienced agent saw him in the stairwell of a building, playing with a toy gun, and shot him.

“The NYPD has killed my son and I’ve fought for recognition for 22 years.”

Hawa Bah also feels let down. Every day, when she sets foot outside her Harlem apartment, there’s a chance she might bump into the cops who killed her son, Muhammad, four years ago. The DA decided not to prosecute them. Bah, who immigrated from Guinea to the US five years ago, explains in tears what happened.

“My son called me and he sounded sick and confused. I rushed to the apartment. When I saw him, I knew he needed help, so I called the ambulance.”

But instead of paramedics, police officers arrived at her door.

“I told them my son needed psychological help but they pushed me aside.”

Muhammad had barricaded himself in the apartment and according to the NYPD he opened the door naked and armed with a kitchen knife and tried to stab a cop. The police shot eight bullets, one to the heart and a bullet in his head. Self-defence, the police claimed. However, according to Bah there was no knife. The NYPD could not produce the weapon; they said Hurricane Sandy had damaged the storage unit with forensic evidence.

“Muhammad was not a criminal; he was a working student, a loving guy who was always there for others. He needed medical help, but instead he was slaughtered like an animal. The NYPD has never apologised. They see us as slaves that you can kill when you want. Don’t they know that slavery was abolished?”

New York Hip Hop artist KRS-One rapped in 1993 in Sound of Da Police about the unmentionable: the unresolved history of slavery in the US and how it has had a formative effect on the organisation of the police.

The overseer rode around the plantation

The officer is off patrolling all the nation

(…)

And if you fought back, the overseer had the right to kill

The officer has the right to arrest

And if you fight back they put a hole in your chest!

Several historians, including Victor E. Kappeler, professor at the University of Eastern Kentucky, write that the predecessor of the American police were slaves patrols and night guards. They had to catch escaped slaves and return them to their “rightful owner”. When the first police forces were established between 1820 and 1850, they were mainly employed in the suppression of slave rebellions and race riots. Monica Dennis, a New York Black Lives Matter activist, believes that that history is still felt today:

“Our capitalist society is built on the exploitation of black bodies. It is inconceivable that black people will decide who they are and what they do. That’s why there is so much surveillance in black neighbourhoods.”

The City Hall Park occupiers also claim the police is a continuation of the overseer on the slave plantations. They’re demanding, among others, that the NYPD budget should be re-invested in communities of colour in New York.

It’s unlikely that James O’Neill, Bratton’s handpicked successor, will calm the frayed stand-off between the occupiers and the officers. O’Neill is a strong supporter of neighbourhood policing, which, say his opponents, boils down to broken windows-based harassment of minorities. As long as there is no recognition of the “colour line” that divides Americans, non-white New Yorkers will, despite reform efforts, remain victims of racist policing policies. DM

* Not her real name.

Main photo: Human rights lawyer Chaumtoli Huq was arrested in 2014 on “broken windows” grounds. Photo by Charles Meacham.