Ruth Hopkins reflects on her recent visit to the United States of America, where processes of truth telling reminded her of its history of slavery and lynching. She learned that it can actually be destructive not to acknowledge the pains, horrors and atrocities of the past.

It is a natural human reaction to look away when confronted with injury or suffering. In this era of mass media where drowned refugee children wash up ashore and onto your screen and where ISIL decapitations flood the internet, this reflex can translate into “misery fatigue”, the feeling one wants a break from the constant stream of human suffering the media feeds us. This reflex predates the era of mass media; those who have been physically or mentally injured often want to escape the memory of the pain.

While I was in New York, I had the privilege of attending a benefit of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) hosted in Manhattan.

At the benefit, EJI’s director Bryan Stevenson presented the Champion of Justice 2016 to Mamie Kirkland, a 107-year old survivor of a lynching that took place in Ellisville, Mississippi in 1916, when she was seven years old. Her son helped her onto the stage. With her head just about peeking above the lectern, she vividly related to an enraptured audience the chilling events that uprooted her life a century ago.

Kirkland said she could never forget what happened that day. She remembered her father coming home and instructing her mother to pack their bags and get the children ready. Crowds had gathered, calling for his and his best friend’s lynching. Her father left immediately, her mother ushered her five children onto a train the next morning. The family made it to St East Louis, Illinois in one piece. Mr. Hartfield, her father’s friend, however, decided to return to Ellisville, where the threat was carried out: a mob shot, hanged and burned the man, because he had allegedly raped a white woman.

This accusation, Ida B Wells pointed out in her book Southern Horrors, Lynch Laws in All its Phases (1892), was often barely supported by facts, but rather fuelled by the hysterical fear of “miscegenation”, interracial relationships.

As Kirkland stood there, her petite frame, fragile voice and heart-rending memories were met with quiet sobs and the dabbing of tears by people seated around me.

“I didn’t even want to see Ellisville, Mississippi on a map,” Kirkland said, she preferred to not return to the site of such pain and suffering. However, EJI’s research into lynchings changed her mind.

Aiming to address the lack of commemoration of the legacy of racial terror, the EJI has documented how many lynchings have taken place in the southern states. Last year, they released this report, that provides proof of more than 4, 000 lynchings that took place in 12 states in the South – a gruesome figure that is barely included in history books or part of historical remembrance in the South.

In the report, EJI referenced Mr Hartfield’s case and when Mrs Kirkland’s son read about it, he contacted them. Hartfield was his grandfather’s friend whom he had heard so much about. He convinced his mother to return to Ellisville. So, last year, on the spot where Mr Hartfield had been hanged from a gum tree, several family members and EJI attorney Jennifer Rae Taylor (who spent some time with the Wits Justice Project) held hands and prayed together to remember the atrocities both the community and the witnesses seemed to want to forget.

This act of remembering, of not looking away, is central to EJI’s work.

“Public acknowledgment of mass violence is essential not only for victims and survivors, but also for perpetrators and bystanders who suffer from trauma and damage related to their participation in systematic violence and dehumanization,” the organisation wrote in the report.

Currently, at the tail end of the first African-American president’s term, the denialist interpretation of history seems to be unravelling. The First Lady recently stated that she wakes up every day in a house built by slaves. Authors such as Ta-Nehisi Coates and Michelle Alexander have written groundbreaking books and articles on the tangible and enduring legacy of slavery in prisons throughout America.

EJI has announced plans to build a national monument for victims of lynchings and they want to open a museum that tracks the evolution of slavery into the disproportionate mass incarceration of black people. The Black Lives Matter movement is making waves and some authors posited that a Truth and Reconciliation movement is taking root all over America. Despite these achievements and plans, Trump’s election seems a dark harbinger of times to come.

Stevenson often references this country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as an exemplary model for post-genocidal countries.

But, the student protests that have rocked and most probably will rock the nation again, beg the question if the “post-1994 rainbow project”, built on the concept of reconciliation instead of revenge, has not failed dismally.

The rainbow project might be flawed, unfinished or outright nonsense. But my stay in the US taught me that the lack of truth telling, not acknowledging the pains, horrors and atrocities of the past, is hugely destructive.

On Confederate Memorial Day in Montgomery, all shops and banks are closed, as it’s a public holiday. The confederate flag flies and people dress up in historical civil war costumes, to honour the soldiers who died defending slavery.

That act of remembering and honouring seems near criminal when Montgomery’s history is taken into account. Montgomery was the capital of the domestic slave trade state before the civil war. The domestic slave trade was fuelled by ever expanding plantations in the South and their demand for labour, which skyrocketed after the transatlantic slave trade was abolished in 1807. In Alabama, the slave population increased from less than 40, 000 in 1808 to 435, 000 in 1860. After slavery was outlawed, 363 racial lynchings took place in Alabama between 1877 and 1950, according to EJI’s research.

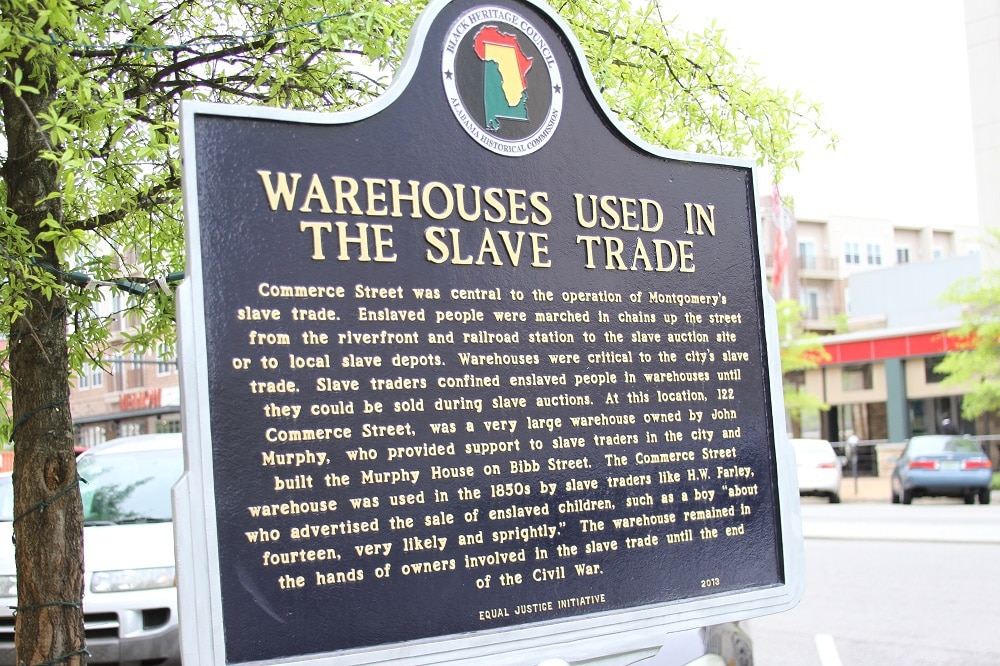

In Montgomery, it is just the markers that EJI fought to erect, that remind the visitor of this bloody past. Many more plaques scattered around town educate people on Alabama’s proud past as the capital of the confederacy.

Stevenson compares this demonstrative amnesia to the Germans, who built a Holocaust memorial in the middle of Berlin, to remind everyone: never again. “Imagine if the Germans would commemorate the Nazis? That would be absurd. We are a post-genocidal society without any recognition for the atrocities of the past,” says Stevenson.

In South Africa, at least, there is a vociferous, dynamic debate about race, racism, land, wealth and (in)equality. And this might not be so impressive if you look at the damaging legacy of apartheid: enduring inequality, poverty, corruption, racism and exclusion. But I still think it is a start to a better future.

Published in The Daily Vox