He was the only man with the power to unite my militant black power group and his civil rights movement. Then, 49 years ago today, a single bullet changed history. By John Burl Smith, as told to Ruth Hopkins

In the summer of 1967, I was back in my hometown, Memphis, Tennessee, after serving two years in Vietnam. I was a “young blood,” 24 years old, full of hope and promise. I had a job at the defense depot, owned a car and rented my own pad. I lived a bachelor’s life and loved every second of it. My childhood friend, Charles Cabbage, who grew up with me in Riverside, a neighborhood on the north side of Memphis, had also returned home. “Cab,” as we called him, had graduated from college and was enraptured by the Black Power movement.

One sweltering evening, Cab and I had an intense discussion about Black Power while driving in my car. He had joined the movement, but I felt those cats lived in a make-believe world. I joked, “You don’t even have a job, with your broke black-power ass, you should have learned how to make some money when you were getting an education.” Cab responded with a rant about how black people should be in control of their communities, because the white man would never let us determine our own destiny. I didn’t understand his discontent. Racism, in my mind, was perpetrated by a few individual white folks.

As Cab and I debated these issues, I pulled into a gas station in Riverside. A white attendant started filling up the tank. When we were leaving he said, “I see you don’t have a gas cap. I can sell you one for a buck.” I had lost three previous gas caps at this very station. Every time, the attendant had sold me a new cap. But now, I took a closer look at the guy and saw something bulging under his uniform. He had stolen my gas cap! Unable to contain my indignation, I shouted, “I’m calling the cops!” When they arrived, they ignored me, heard the attendant out instead, then arrested Cab and me.

Even though a judge later dropped the charges, I was shocked at this treatment. The gas cap incident was a turning point in my life. I realized racism was not the fault of a few bad white people; it was a systemic ill. I became more interested in the Black Power movement. Cab and I started organizing in poor black neighborhoods for Memphis Area Project (MAP South). Later, along with another friend we founded the Black Organizing Project (BOP) and developed a community unification program, which addressed socio-economic needs in the black community.

We started organizing in high schools and got a lot of youngsters involved. We also recruited at the University of Memphis, a traditionally white institution with only a smattering of black students. In the cafeteria there, all the black students huddled together with their lunch trays in a corner. It infuriated me that the white students walked through that space like they owned it, while the black students looked like they were scared, walking on eggshells. I moved to the center of the room, climbed on a table and at the top of my voice I shouted: “What is going on with you, black students? Some of you are so afraid; you are standing around, holding your trays. Black people are dying and fighting for equal education. You should have access to the student union; you should be organizing to get access to everything this school is offering. You need to be fighting for your rights!” The students looked at me in amazement. Then security entered the room and frog-marched us to the principal’s office, where we received a stern warning never to come back.

Our university and high school activities were aimed at recruiting people to help us achieve BOP’s main goal: uplifting the poorest of the poor, the communities that had no voice. We would hand out copies of our newspaper, The Voice, to sanitation workers, maids and gardeners on their way to and from work. We would sit with them and chat about poverty and what they could do to resist.

I met Donny Delaney when he was still a high school student. I asked him about the word Invaders, written on the back of his jacket. He told me he watched a futuristic sci-fi television show called “The Invaders,” about aliens invading earth. This was, in his mind, similar to the fate of black people in America. Our ancestors were taken from their homeland in Africa, brought to America and enslaved. They invaded a world populated by white Europeans who didn’t want to share their fortunes. Donny became one of our young organizers. When he died in Vietnam, we changed our group’s name to “The Invaders.” I painted Invaders on my jacket and soon the others followed suit.

The Invaders were not on the same page as civil rights leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Jesse Jackson of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Roy Wilkins, the leader of the NAACP. We found them too passive, called them Uncle Toms.

In the beginning of 1968, we backed Memphis sanitation workers who had taken to the streets to protest their abominable treatment. Black workers couldn’t use the shower in the locker room and didn’t receive equal pay. When two workers were killed on the job, they staged a strike.

We didn’t own guns and were not into extreme violence, but we believed that throwing rocks and bottles at sanitation trucks, setting fires in garbage bins, confronting the police and other acts of vandalism supported the strike.

The strike-steering committee disapproved of our tactics, accusing us of being a violent street gang. But the committee didn’t have a rapport with the workers, while we did. In a move aimed to regain control, they invited Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Memphis to address the striking workers.

On March 18, 1968, thousands of garbage collectors gathered at Mason Temple to hear King speak. They were beside themselves when he entered the pulpit; deafening roars of approval filled the church. King told them they should start a general strike and offered to come back to Memphis to lead a march on City Hall. As the loud cheers died down, he announced: “The Poor People’s Campaign starts here in Memphis!”

Dr. King’s radical stance surprised the steering committee; they thought the Nobel Prize laureate would have a more salving tone, aimed at compromise. But King was preparing a radical campaign to take the struggle for the rights of poor black people forward. He wanted to bus in thousands, if not millions, of poor people to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. He envisaged this as the biggest protest ever against the enduring poverty of millions of slave descendants in America.

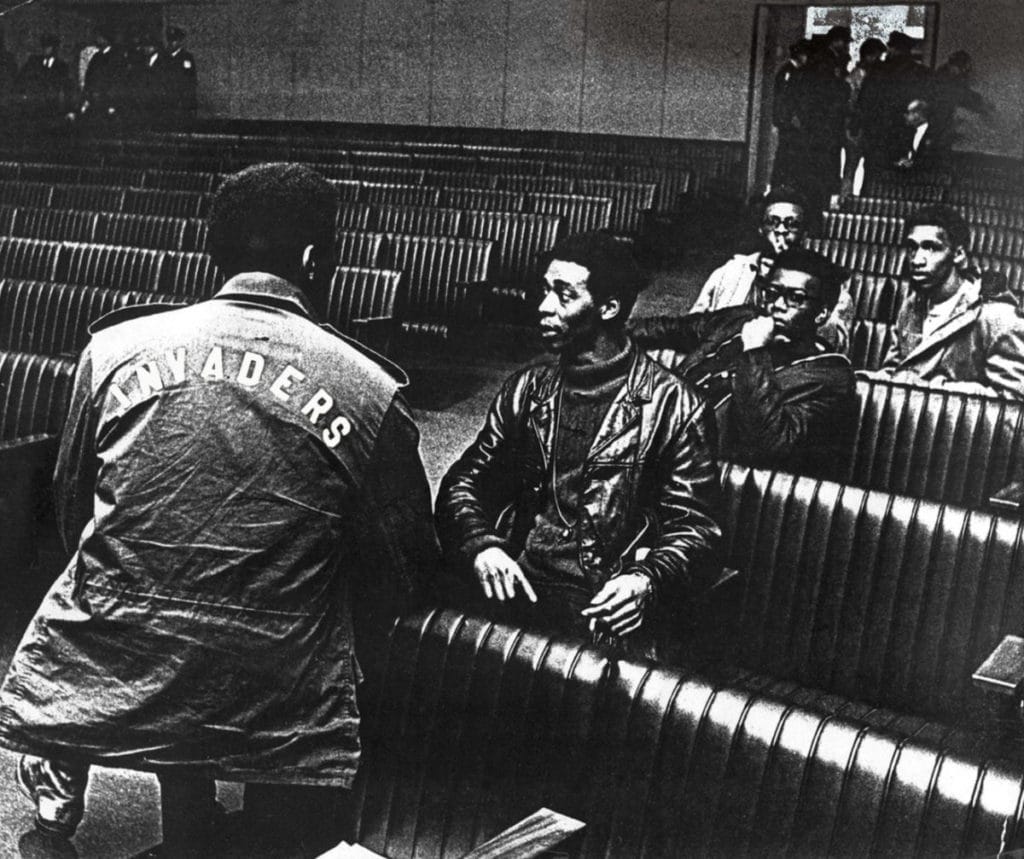

John Burl Smith, left, with his back to the camera, and Invaders co-founder Charles Cabbage, center, gather with other members of the Invaders at Memphis City Hall, ca. 1968. This photo was used in the official poster and banner for “The Invaders,” a documentary directed by Prichard Thomas Smith, which was released in 2016. (Photo courtesy University of Memphis Special Collections)

Because of its strong class undertones, King received little support for his Poor People’s Campaign. Many in his own organization, the SCLC, disapproved of it.

Meanwhile, the Invaders were kicked out of the organizing structures of the strike. The leadership, mostly middle class civil rights activists and religious leaders, felt our ideology was too radical. They wanted to strike a deal with white leaders that would protect their interests.

On March 28, 1968, King came back to Memphis to lead the march. I joined the ocean of people heading north from the Clayborn Temple towards Beale Street. Suddenly, the forward motion came to an abrupt halt; people started bumping into each other. I glanced up and saw police snipers on the roof. Then there was a crashing sound, like an explosion. Everyone started frantically running in all directions. The police immediately laid into the crowd, assaulting them with billy clubs and spraying mace everywhere. The protesters responded by ripping off the placards that read “I AM A MAN” and using the sticks to fight back.

In the middle of this mayhem, a car stopped at the sidewalk and the driver urged me to get in: “I saw your Invaders jacket, so I pulled up.” He had just come from the front of the march and told me what he had seen. “There was a line of police across Main Street. They stopped the march. As we waited, a police officer grabbed a man and threw him up against a wall. The cop swung his club, missed and hit a glass window instead, which caused the explosive sound that had everyone running.”

The media blamed the Invaders for starting all the trouble. Some civil rights leaders claimed the Invaders were bent on destroying King’s non-violent reputation.

To our surprise, the day after the march, we heard that Dr. King wanted to meet with us. Cab believed we could trust him, but I was not so sure, given the SCLC’s stance. Dr. King told Cab he knew we were not responsible for the riots, and that he wanted to work with us on the Poor People’s Campaign.

This was huge news. Considering that everyone was blaming us for the riots and that the FBI had been hot on our heels for a while, we felt it was safer to relocate from my apartment, which had been ransacked several times, to the Lorraine Motel, the only black-owned hotel in town.

* * *

One of the most fateful days in history, April 4, 1968, started out hopeful. King had returned to Memphis the previous day and checked into the Lorraine Motel.

About eight Invaders, including Cab and me, met with Dr. King at one p.m. in the dining hall above the motel office. We sat in a semi-circle and he took a seat in the middle, facing us. We were ready to work with him to make poverty issue number one in America. King told us that he was very sorry we were being blamed for the violence during the march, which he had witnessed the police inciting. He then moved on to discuss how to work together in the Poor People’s Campaign.

We agreed to get other black power groups in the country involved, and to serve as marshals during the march on Washington. King had worked with Black Power groups before and had publicly declared that the civil rights movement had to try to communicate with these youngsters, to give them a voice. He had no qualms about aligning himself with us, despite the mainstream media and everyone else accusing us of being a violent street gang. He saw through those lies and knew that we shared his anti-poverty agenda. He saw us as allies.

King promised to help us fund our community unification program and in return, we agreed to a non-violent approach. The Invaders were broke, and to us, it was way more important to finance our anti-poverty activities than to hang on to a militant approach. In high spirits, we headed back to our room.

Everyone agreed we should work with King, but there were concerns about whether his organization would go along with the plan to collaborate with us. After King left town, we reasoned, what else other than his word did we have? Cab and I were tasked with hashing this out with King.

We knocked on his door and a haggard looking King opened. He was alone in the room. His public persona had dissipated and we saw a different man – tired, stressed and restive. He motioned for us to take a seat on one of the two beds in the room. He sat on the other, facing us.

King spoke about his Poor People’s Campaign and how he was struggling to get his colleagues on board. We spoke about our troubles: the infighting that had led to our exclusion from the organizing committee of the strike, the slanderous things civil rights leaders had said about us, the constant harassment by police and the FBI. King took a long look at us; his eyes rested on me as he rubbed his chin.

After that brief silence he told us he feared for his life. A friendly official in the justice department had set up a covert meeting between King and J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI. Hoover had said, “Your mouth is going to get you in a lot of trouble.” King told us he realized that Hoover might actually try to kill him.

As our meeting was coming to an end, we explained that we were really struggling financially. We couldn’t organize without money. King reached over and placed a hand on my knee. He said he was willing to provide assurance. After making a phone call, he handed us a promissory note to the value of $10,000, authorized by the National Council of Churches.

I left the room with my head in a cloud. Here I was, the great-grandson of the first in my line to be born free and now I was working with the most famous civil rights leader in the world. Together, we were going to play a major role in bringing social change to black people.

King looked less tired as he said goodbye. He smiled and thanked us for our support. We shook hands and headed back to our room, where we were met with cheers. Everyone was eager to start the campaign.

I took a bus back to my crib with some other Invaders. We spoke excitedly about the new plans and how our lives were about to change. It was only 45 minutes after our meeting when I switched on the TV in my apartment and we heard the devastating news: Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated at the Lorraine Motel.

We were gutted. We all knew his life was on the line, but we never thought this would really happen. All this man spoke about was peace, love and understanding.

If King hadn’t been killed, we would be living in a different world today. He fought the unjust poverty of millions of African Americans with such determination. He held the federal government responsible for the poverty of black people in a way no one has since.

The Invaders didn’t stop. We worked as marshals for the Poor People’s Campaign, which went forward in May and June of 1968. The money King promised us never materialized, but we felt we had to honor our promise to him nonetheless.

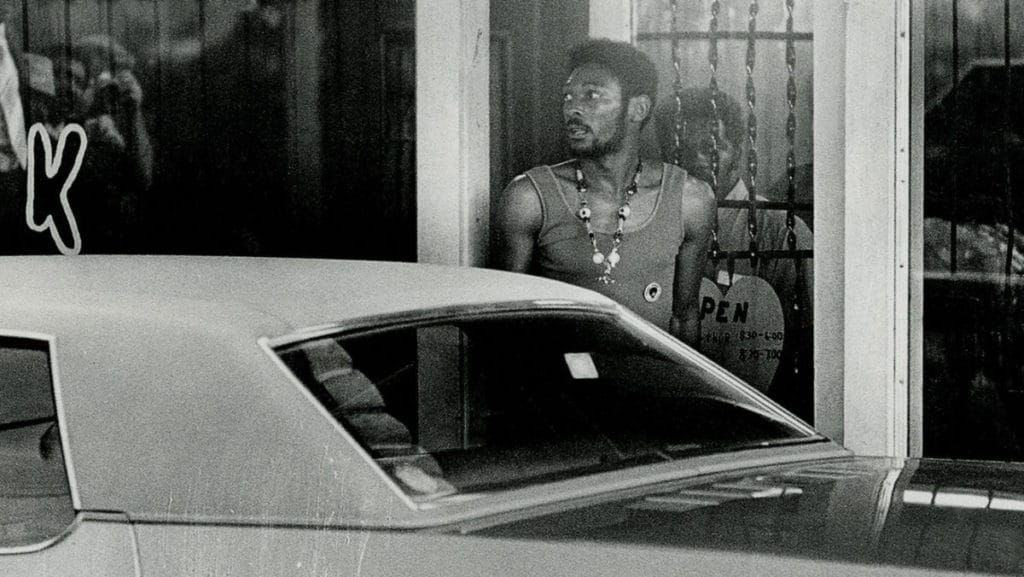

Main Photo courtesy Associated Press