I broke the story on a private prison in South Africa where guards inflicted horrendous abuse. But to really understand what happened, I needed to talk to the torturers themselves.

“Inmates were lying everywhere,” says Sipho Kumalo, a former member of the Emergency Security Team (EST) at Mangaung prison in Bloemfontein, South Africa. “Ninjas were all over the place, shocking, kicking, .” On the inside, members of the EST – a squadron of guards in riot gear – are referred to as “Ninjas” because of their black uniforms. “Klapping” is an Afrikaans word for hitting or slapping.

“I saw blood on the floor,” Kumalo continues. “Those prisoners had to feel who was boss. And we made them feel. They were going to realize they could never do this again.”

The EST’s duties range from quelling gang fights, to putting out fires, to dealing with inmates who are perceived as being difficult, problematic, or too vocal. Whatever the context, Kumalo says, they know how to “sort out” a prisoner.

Kumalo – a 43-year-old father of two with low set eyes, full lips and round cheeks – speaks softly, sometimes halting mid-sentence as he searches for the right words to describe his thoughts. He worked at Mangaung – a private correctional facility run by British security behemoth G4S – until two months ago when, along with seven other EST members, he was dismissed, allegedly for failing to comply with an order, although he believes it was because he has been critical of the company.

Like other former penitentiary employees – as well as inmates – interviewed for this article, Kumalo asked to have his name altered to protect against retaliatory acts.

He was on duty November 19, 2012 when the EST was called to deal with fires that prisoners had set in the isolation unit. As the flames began to grow, Kumalo and his EST comrades were in another block where an inmate was holding a doctor hostage in his cell, threatening the man’s throat with a shard of a broken fluorescent light bulb.

“There was total chaos in ‘Broadway’ – the isolation unit,” says Kumalo. “The prisoners had set fire to the cells while they were still inside, so we had to unlock them first and douse the fire.”

Kumalo says he was furious when he heard the prisoners had started the fire. “I thought: ‘Who would do this? Which adult would ever behave like this? treat us with such disrespect?’ So we beat the shit out of them.”

The G4S firm boasts a global reach, promising to “secure your world” in over 110 countries. The company employs over 585,000 people and hauled in $8 billion in revenue in 2016.

G4S was awarded the contract to build, maintain and run Mangaung prison in 2000, a year before it opened its doors. According to G4S, Mangaung is now the second-largest private prison in the world, housing about 3,000 inmates in a maximum-security setting.

I visited Mangaung for the first time in 2012, following up on several letters inmates had sent to the organization I work for, the Wits Justice Project, a group of investigative journalists based at Wits University in Johannesburg, who research and write about the criminal justice system. Inmates contact us about a wide variety of issues, ranging from problems in their appeals process to prison conditions to health care issues, torture and assault, and the lack of education opportunities. Prisoners from Mangaung wrote about electroshocking, lengthy isolation, and forced medication with anti-psychotic drugs.

I returned to Mangaung countless times, and over the years interviewed more than 100 inmates, dozens of warders (as prison guards are known in South Africa) and several other sources. A pattern of abuse emerged from their stories: the Ninjas would be called to take inmates to either the hospital or Broadway, where there are CCTV blind spots. There they would order inmates to strip, place them on a metal bedframe, pour water on them and then shock them with their electrified shock shields. Inmates were also injected against their will with anti-psychotic drugs, often when they had no history of mental illness.

Another form of crowd control practiced by the prison management was the lengthy isolation of inmates. Several men had been held in solitary confinement for up to four years.

The prisoners were fed up with this treatment. Their repeated complaints about the abuse had fallen on deaf ears; the management not only ignored their complaints, but stymied their attempts to report the assaults, injections and isolation to the police. The inmates felt their last and only resort was to disrupt the prison operation. Ntzitzi Nyanga is one of the prisoners who started the fire in Broadway. “About five or six men came to my cell and ordered me to strip naked,” he says. “They handcuffed me and then threw me on the floor and started kicking me, everywhere on my body. They poured water on me and electroshocked me with their shields.”

(A 2009 murder conviction landed Nyanga in the G4S-run prison, where he stayed until 2014, when he was acquitted on appeal.)

The Ninjas beat Nyanga up so badly, he can now no longer see with his left eye and he sustained a broken rib and nose.

“They’re not humans, they’re monsters,” he says.

But for years leading up to that violent outburst, the guards had repeatedly notified the prison management of a lack of security and safety in the prison. The union presented management with a list of 30 detailed complaints: a female warder had been raped; another warder died, three months after he had been stabbed for the twelfth time; an activity officer was kicked in the head and sustained an eye injury, which meant she always had to wear sunglasses, even indoors. They also complained about racism. Black guards were sent into the units with violent inmates, unarmed, while most white people were placed in safe management or admin positions. The disgruntled workers wrote in their petition that white workers were promoted more and earned more. The prison director, Johan Theron, dutifully received the complaints, but did nothing to address them.

The resistance from both the warders and the inmates did not convince the prison management that change was needed. Unprecedented levels of violence spiraled into utter chaos in the prison.

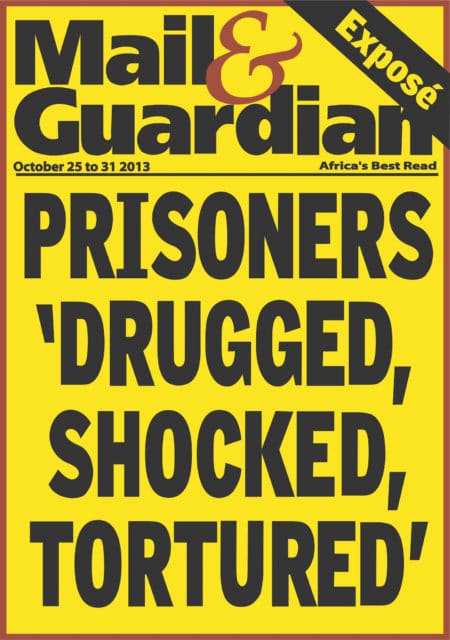

In August 2013, the workers staged a collective sick leave, followed in September by a full-blown strike. The prison operation ground to a halt when G4S fired the striking workers, who made up two thirds of the workforce. Inmates were locked in their cells 24 hours a day, often missing meals. When G4S hired unqualified guards to replace the dismissed ones, the department of correctional services stepped in and took control of the prison, much to the dismay of G4S. Two weeks later, my exposé of torture and abuse hit the press.

While G4S categorically denied that any form of torture had ever taken place in the prison, the department had a more robust approach to the prison drama. The then minister of correctional services, Sbu Ndebele, condemned the situation and promised to investigate the allegations in my article, and publish a report shortly thereafter. However, that report has, to this day, not been released. The minister was quickly replaced by Michael Masutha, who described Mangaung as a state-of-the-art facility in August 2014, when the department handed back control of the prison to G4S. Reluctantly, they rehired the 330 workers who had previously been dismissed. Kumalo was one of them.

As a G4S employee, Kumalo struck prisoners with batons, broke bones, and poured water on naked men bound to a metal bedframe. He took out his electrified shock shield with an output of 6,000 volts and placed the shield on genitals, heads, backs, and chests. He pressed the trigger – until the screaming was too much to bear.

“I think back to the things I did and it haunts me,” Kumalo says. In his nightmares, there is blood running in rivers on the floor. “I tried explaining it to my wife, but she just says, ‘don’t talk to me about your traumatic prison work, I don’t want to know.’”

* * *

Sipho Kumalo was feared among inmates. But on the inside, he says, he is still the quiet introverted farm boy who grew up hungry.

Kumalo’s parents were poor farm workers who could barely feed their brood of ten. For years, Kumalo would wince when he heard the school bullies talk about him like he was a simple hick with no brains. “Don’t listen to him, he’s a dumb farm boy,” they’d say. Kumalo swallowed the insults, kept his head down, and became determined to be the first in his family to matriculate in high school.

“I had an inferiority complex,” Kumalo concedes. South Africa was under Apartheid rule at the time. His father’s white bosses would call him and his family , which is essentially the South African version of the n-word. “He was a stubborn man and would get into fights… I saw my father come home with a bruised face, time and again.” His father continually had a hard time holding down jobs.

“My parents had no idea who Mandela was,” Kumalo explains. “They didn’t read, they were simple people.” One day he saw youngsters in the center of town throw rocks at the police. All his life, he had been taught to run away from policemen. “I thought they were crazy,” he says of the kids.

As a teenager, Kumalo experienced something of a political awakening. His English teacher began to discuss the role whites played in the history of South Africa, how they laid claim to lands there. Kumalo also read up on Black Power. A seed had been planted.

He realized that the history of his country was intimately linked to the humiliating treatment of his father. A deep-seated rage welled up. “I developed an absolute hatred of white people. I vowed never to work for a white [boss], like my father [did].”

So when the class bullies called him “farm boy” again, it punctured a hole in his pent-up repository of anger, now amplified through his newly found consciousness of the violence of colonialism and apartheid. Kumalo positioned himself at the school gate to confront the bullies, three boys. When he saw them approaching, he closed the gate, effectively locking them into the schoolyard. One by one, he beat them down.

When he finished high school, Kumalo moved to Bloemfontein in search of work. He survived on odd jobs and slept on friends’ couches, grateful for the kindness of the people around him. But as time went by Kumalo felt he was a burden on his friend’s family, and he moved, living with a small-time criminal for a while.

When he picked up the glossy G4S recruitment brochure at a local library, his expectations were low. But he went for an interview and made it to the second round.

“I didn’t even know what the word ‘contract’ meant when they offered it,” he admits. “I felt, . It was a huge turning point in my life. I was given an opportunity to escape the life my father led.”

During his training he was taught that the Emergency Security Team was always to be in charge.

“You tell the inmates what to do, not the other way around,” he says. He learned how to use legally mandated “minimum force” when restraining a violent inmate. The trainees administered shocks to each other, so they would know how it felt.

“You know, it can knock out a cow. Do you know how big a cow is?” he asks incredulously. “It’s like you’re hit with an iron rod.”

When he started his job, he was taught other, more sadistic, tricks. Kumalo says the security manager of the prison, who has been implicated in several violent incidents himself, taught him about the water, during his first few months on the job. “You know, if you mix electricity and water, it hurts.” He says. The manager also taught him: “Shocks hurt a lot more if they’re applied directly to the skin.”

Malose Langa is a psychology professor at Wits University and has acted as an expert witness in a court case the inmates filed against the company and its subcontractors. In that capacity he interviewed many G4S inmates. “What haunts these men still, is not the physical violence, but being stripped naked before men and sometimes women warders. This, in their experience, is a lot more traumatizing than any physical pain, because it is so profoundly emasculating,” he says.

Kumalo describes endless cruelty: how the “dark room” – a soundproof suicide prevention cell in Broadway – was exactly that, dark, but you would see the victim when you pushed the trigger on the electrified shield, as little sparks would throw some light on the prostrate, often naked, man who was about to get a huge trashing.

“There was this one guy,” Kumalo begins one story, “a big guy, a general of a prison gang who ruled with an iron fist over the other men. He was known for his strength and violent disposition.” The Ninjas took him to the dark room where they beat, kicked and electroshocked him. He begged them to stop. “To hear a big man like that beg so desperately, that stayed with me.”

Kumalo has shown me group text chats in which Ninjas gloat after inmates are beaten down. “You gents are my heros [sic],” a security manager wrote to them one day after such an incident. “Warriors are never trained to quit or give up. What we all witnessed today was character. EST won the fight. Period. I’m sweating it out at the gym while he is licking his wounds like a little bitch that he is. Little did he know what he was attacking. But now he knows about the beast that I am.”

“He got it,” another EST member wrote.

* * *

“I used to be a friendly guy, shy and caring,” Kumalo says, sitting on the couch in his living room, his legs folded under his body. “I never got into fights or trouble. But this prison work has changed me. I feel angry a lot of the time. I have horrible nightmares. The terrible things I have done…” He trails off. “And I bring it home. I take it out here.” Later, he tells me he once hit his wife after a long, frustrating day at the prison.

Kumalo has two daughters, who dart in and out of the room. They have both inherited their parents’ round features. The older one keeps to herself, but the younger girl cuts through the conversation to show her clothes, earrings and a book. While her dad is talking about his nightmares and anger, she climbs up on my chair and squeezes her bum into my seat.

“I realized what we were doing was wrong,” Kumalo says. “I talked to inmates, asked them why they behaved the way they did and I found it was more effective than all the violence,” he says, tiredly rubbing his forehead.

About four years ago, Kumalo tried to reason with his colleagues and they agreed that they were going overboard. “When I raised it with the manager, all he said was, ‘are you questioning my authority?’ It felt like a threat.”

Darkness has fallen over the township. It’s suppertime in the Kumalo household. His youngest daughter reappears from the kitchen with a bowl of pap and chicken, which she gobbles up as her father reflects on the legacy of racism and apartheid in his life.

“I ended up in the same situation as my father,” Kumalo discloses. “Sure, I was getting paid a lot more than him, but the white man runs that prison.”

Kumalo leans forward, hands under his chin, elbows resting on his knees.

“A few years ago I realized that they enable the violence because all they care about is that they maximize their profits. They don’t give a damn about us. And instead of taking them on, we are beating down our brothers. And that is wrong.”

His daughter has finished her food in record time and a big, content smile spreads over her face. For the first time she sits still in her chair.

“Apartheid is still alive in that prison,” Kumalo says with a wry smile. “To them, we are all disposable.”

Published in Mail & Guardian